Shopping, Shaw’s 2004 temporary site specific installation commissioned by Canterbury City Council and Land Securities plc as part of the Whitefriars Public Art Programme in Canterbury, also engaged with notions of consumerism and desire. On the last day of the exhibition, Shaw invited the public to take away one of the individually numbered bags that formed the installation. No purchase necessary.Have an artwork to take home. Cherish it or spoil it. You choose the value of it.

If Shopping let you consume the object of desire then Virgin Archive lets you stand centre stage as the artist and transform it.

In her application for funding for Virgin Archive Shaw speaks about providing an opportunity for the people who bought one of her Virgins to ‘…create a piece of art work which will be exhibited publicly…’ going on to say that ‘…this activity invests in the creative talent of artists and individuals.’

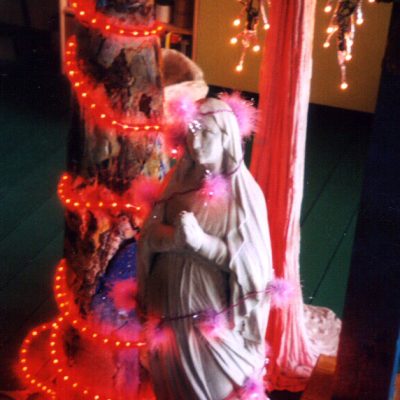

It is an interesting twist to ask people who have acted as consumers to now act as the producers. This element of democracy is a strategy employed by Shaw throughout her work as artist and educationalist. Shaw teaches trainee teachers and Fine Art students. She acts as a facilitator. Throughout the Virgin projects runs a thread of facilitating others to take their own artistic control. Shaw encourages those who purchase a Virgin to re-present her in their home environment, to decorate her as they like, to take artistic control and not simply be a passive consumer.

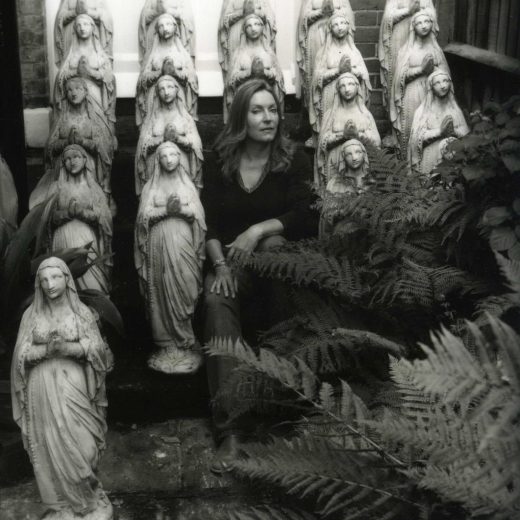

The Virgin Archive exhibition at the Horsebridge Arts & Community Centre in Whitstable, Kent includes all of the images of the purchased Virgins that Shaw was sent. Showing the archive in its entirety is part of this element of democratisation. However, Virgin Archive is still Shaw’s project. She is the curator and the keeper of the work, storing it for future use. The archive maps the geographical locations of the purchased Virgin’s – Australia, Western Samoa, Essex, Whitstable, Brighton, Canterbury, the New Forest and Lincolnshire, and also documents and records the exact physical locations of them – orchard, sitting room, loo, forest, garden. What Virgin Archive also does is document the Virgin as art object. Firstly as Shaw’s original vision of her as part of the Lourdes installations and secondly as her owners vision of her – be it as a kitsch icon bedecked in fairy lights in the corner of the sitting room or as a statue to meditate and pray with, placed in a secluded part of the garden surrounded by flowers and trees.

Virgin Archive touches us on a multiplicity of levels. Everyone who has purchased a Shaw Virgin has entered, consciously or unconsciously, into a dialogue not just with the object but also with themselves. The relationship with the art object (Virgin) has become deeply personalised and Virgin Archive celebrates this transformative relationship both on a literal and conceptual level. The inclusivity of Virgin Archive asks us to view the resulting images not just as documents but also as works of art. It also encourages us to question what value we place on objects, artworks and artists, and why. The questions surrounding archives – Why create them? What is the purpose of them? – link us back to this idea of the democratisation of the image and artistic production. Shaw, although still in control of how the work is shown and used in the future has also encouraged others to share in the artistic re-interpretation of the object of desire: the concrete, ornamental Virgin.

Virgin Archive represents a pause, a place to stop and re-examine where Shaw started. It offers the consumer the means to reflect alongside Shaw on this exploration of consumerism, the manipulation of the consumer and the manipulation of the image.

Liz Kent 2006